At first glance it seems like the debate on reusable and disposable plastic in the NHS is an obsolete discussion. We’ve all seen the headlines warning us how unsustainable and terribly polluting plastic is as a finite resource. Plastic should just be avoided at all costs, right? In "Delivering a 'Net Zero' National Health Service”, it was claimed single use plastic devices make up 1.4% of all supply chain emissions, equalling around 231.4 tonnes of CO2 equivalent.[1] The answer seems easy and obvious. Stop using single use plastic in all industries including the healthcare sector and switch to non-plastic products to reduce waste, CO₂ emissions and the associated costs. I’d encourage readers to think again.

Plastic has the potential to be an ally in the NHS’s net carbon zero goals (2040 for direct emissions and 2045 for indirect emissions i.e. the supply chain) and not as bad as we’ve been led to believe.[2] Plastic is irreplaceable within the healthcare industry due to the versatile textile’s sterility, robustness, and antimicrobial features. It can easily be injection moulded into a smooth device which is extremely important in infection control when any bumps or imperfections in the medical device could risk infections and thus is necessary to guarantee safe medical practices.[3] In some cases, it’s the only material given legal clearance for medical use because it’s the only material that can feasibly be used. If plastic was to be scrapped the legislative complications and the struggle to find a suitable alternative would cause great logistical challenges.

Many are aware It’s not possible in clinical practices to scrap single use plastic devices. However, there is potential to reduce the reliance on disposable devices if we rethink the coding on medical devices. Reusable devices are identical, yet single use devices are often favoured because they are cheaper. In some cases, devices are only used once to guarantee no cross-contamination or risk of patient injury if the device fails but there is scope for sterilising and decontaminating some devices so they can be put back into the resource economy and reduce the volume of waste. [4]

The answer is to reduce our use of plastic – not get rid of it and replace it with something else – and where possible swap to reusable devices to prolong a product’s value at the highest level possible and maximise its utility. This is achieved through redistribution, refurbishment and reusing the product if safe to do so. For the most part, the same amount of energy is put into producing reusable and disposable plastic products. They are equal in creation and performance; the most sustainable option is the reusable products as the energy they consume is more efficient given its used for longer, even when considering the cost and energy needed for stock storage. For example, the NHS has ordered circa 61 million single-use tourniquets so far in 2022. If every trust switched to reusable tourniquets, the NHS could reduce their plastic consumption by up to 30 tonnes, reducing their carbon footprint and saving on waste costs.[5] Following the principles of the circular economy, the NHS can reduce their reliance on virgin materials and send fewer consumables to landfill.

Furthermore, plastic triumphs against competing textiles in most Life Cycle Analysis requisites. A Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) is a “cradle to grave” examination of a manufactured product. It considers the total effects on the environment each product creates including the emissions produced in a product's creation, transportation and storage, the energy and water requirements in production, the air and water pollution emitted, the volume of solid waste generated and how this waste is managed.[6] Chris De Armitt, (author of The Plastic Paradox) highlights IN most LCAs, when pitted against other materials designed to carry out the same or similar functionality plastic comes out as the least environmentally detrimental.[7]

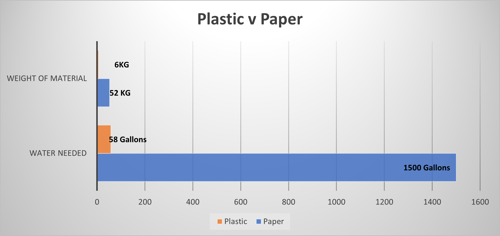

For example, let’s compare paper. To replace 6Kg of plastic, 52Kg of paper is required and for every 1500 plastic bags created 58 gallons of water is needed versus 1502 gallons of water for the paper equivalent.[8] Paper also goes through a pulping and bleaching process that aren’t necessary in plastic manufacturing. Paper often gets a good reptation because of its recyclability yet when paper is sent to landfill it struggles to decompose at the same rate as plastic.[9] For example, a newspaper at Clinton County landfill site in Pennsylvania was still readable 27 years after it had been printed.[10] This is due to the lack of oxygen, air and light, instead of decomposing it secretes carbon as it sits in municipal waste piles. Most of the population including NHS staff know which recycling bin to put paper in but there is confusion over the destination of plastic. Fixing the recycling conundrum will create a more reliable product that can be sustained within the circular economy for longer. Recycling can catch valuable resources before their full potential as been utilised, but its real significance lies in the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, and the minimization of waste going to landfills.

If the NHS are to reach their net carbon zero ambition by 2040, demanding on 8% decrease year on year, plastic needs to remain within their infrastructure.[11]

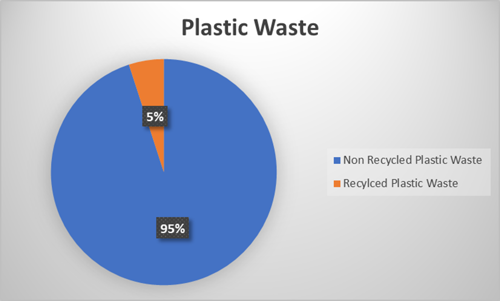

So, what is the solution, how do we use plastic more efficiently within the resource economy? We must tackle the culture of overconsumption, misconceptions about waste streams leading to poor end of life management and dually invest financially and innovatively in adequate infrastructure solutions so that plastic can be successfully repurposed and recycled. Having the right infrastructure is paramount. Recoup have reported a bottleneck within the recycling infrastructure, stating an increase in reprocessing plastic packaging is desperately needed, suggesting increasing the current recycling infrastructure by five times for household-like plastic packaging and nine times for food grade plastic packaging.[12] Plastic contributes to approximately 23% of all NHS waste, (133,000 tonnes), costing a yearly average of £5.75 million to dispose of, with only 5% of all plastic waste currently being recycled.[13] There is a great opportunity to vastly increase this percentage. Investing in a greater volume of sophisticated and conveniently located infrastructure in the long term will result in carbon savings and cost reduction as the volume of waste being incinerated is reduced as well as putting the £50 million the NHS spend on carbon permits annually back into the budget. [14]

‘Delivering 'a Net Zero' National Health Service’ stated “bio-based polymers will produce significant savings of 498 ktCO2e in the future” this is significant if they are disposed of in the right bin but at the moment there is a lack of infrastructure which is causing more emissions when they invertedly get sent to landfill.[15]

The NHS were the first healthcare service in the world to pledge net carbon zero.[16] They were the first to write it into legislation too with the Health Care Act 2022.[17] The organisation is passionate about achieving this goal. Yet at no ill intention of healthcare professionals, these misconceptions around plastics are creating unfavourable results preventing the NHS from achieving true sustainable practices and subsequently cannot optimise their efforts to reduce their carbon footprint.

Now, single use plastic shouldn’t be given explicit praise because of its greener credentials, where possible all single use products should be eradicated from our resource economy by questioning if its purpose holds any value to us. Like do we really need a plastic straw? Should we be happy to discard it just because it's easy and inexpensive for us as a consumer? The green choice isn’t to replace this with single use paper straws or reusable silicone alternatives but to use no straw at all.

Swapping disposable products for reusable products will not allow the NHS to reach their net zero emissions target but will form part of the overall solution. Yet replacing plastic with other alternatives will be detrimental especially when it comes to single purpose products.

The most sustainable mindset doesn’t ask us to rethink the material we use but how we manage and treat the materials within our economy. We should be asking ourselves if a product needs to be created and enter the system in the first place.

Blog References

[1] Delivering a ‘Net Zero’ National Health Service (2022) NHS choices. NHS. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/a-net-zero-nhs/ (Accessed: November 11, 2022).

[2] Discover how the NHS is becoming greener (2022) NHS choices. NHS. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/ (Accessed: November 11, 2022).

[3] University of Exeter (2022) Accelerating the transition towards a net zero NHS: Delivering a sustainable and resilient UK Healthcare Sector. Available at https://cdn.ca.emap.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2022/03/Accelerating-the-transition-to-a-net-zero-NHS-delivering-a-sustainable-and-resilient-UK-healthcare-sector-Philips-UKI-and-Exeter-University-compressed.pdf. Page 19. (Accessed: 28 October 2022)

[4] Chapter 1: Standard infection control precautions (SICPs) (no date) NHS choices. NHS. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/national-infection-prevention-and-control-manual-nipcm-for-england/chapter-1-standard-infection-control-precautions-sicps/ (Accessed: November 11, 2022).

[5] Supporting The NHS This Plastic Free July (2022) NHS choices. NHS. Available at: https://www.supplychain.nhs.uk/news-article/the-nhs-supporting-plastic-free-july/#:~:text=The%20NHS%20has%20ordered%20circa%2061%20million%20single-use,the%20supplier%E2%80%99s%20recommendation%20of%20up%20to%2025%2C000%20reuses (Accessed: November 11, 2022).

[6] British Plastics Federation (2022) Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) - A complete guide to lcas, British Plastics Federation. Available at: https://www.bpf.co.uk/sustainable_manufacturing/life-cycle-analysis-lca.aspx (Accessed: November 11, 2022).

[7] DeArmitt, Chris. (2020) The Plastic Paradox: Facts for a Brighter Future. Phantom Plastics LLC.

[8] Jordanova, L. (2022) [LinkedIn] 7 October. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:6982056954747641856/. (Accessed: 11 November, 2022

[9] Talk, E. (2019) Do biodegradable items degrade in landfills?, ThoughtCo. ThoughtCo. Available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/do-biodegradable-items-really-break-down-1204144 (Accessed: November 11, 2022).

[10] Centre County Recycling and Refuse Authority (2018) [Twitter] 9 August. Available at: https://twitter.com/CCRRA1/status/1027638821654093824 (Accessed: 11 November 2022).

[12] Recycling Plastic Packaging In The UK - Who Owns The Bottleneck? - Recoup Recycling (2022) . Available at: https://www.recoup.org/news/8223/recycling-plastic-packaging-in-the-uk-who-owns-the-bottleneck (Accessed: November 11, 2022).

[13] Rizan, C. et al. (2021) “The carbon footprint of waste streams in a UK hospital,” Journal of Cleaner Production, 286, p. 125446. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125446.

[14] Fenwick, S. (2021) Benefits of reducing carbon footprint for the NHS, energy saving lighting. Available at: https://www.energysavinglighting.org/benefits-of-reducing-carbon-footprint-for-the-nhs/#:~:text=The%20NHS%20spend%20%C2%A350%20million%20a%20year%20on,which%20is%20approximately%204.8%20million%20tonnes%20of%20carbon. (Accessed: November 11, 2022).

[15] Delivering a ‘Net Zero’ National Health Service (2022) NHS choices. NHS. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/a-net-zero-nhs/ (Accessed: November 11, 2022).

[16] Discover how the NHS is becoming greener (2022) NHS choices. NHS. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/ (Accessed: November 11, 2022).

[17] Health and Care Act 2022 (2022) gov.uk. Queen's Printer of Acts of Parliament. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2022/31/contents/enacted (Accessed: November 11, 2022).

Written By Charlie Dawson