The circular economy is based on 3 principles (definition from Ellen Macarthur foundation)

- Elimination of waste and pollution

- Circulating both products and materials at the highest value

- Regenerate nature

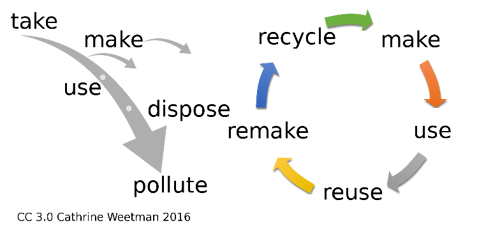

The current system we are using is more of a straight-line economy

Raw materials – production of goods – use of goods – waste (Weetman, 2016)

In a straight-line economy, the earth's natural resources are used to produce a product which is then consumed (once or several times). Once the product is consumed it can then be disposed of, and another product takes its place.

This type of economy promotes cheaper goods and faster production at the expense of our natural world. In a straight-line economy, companies are not focused on the effect their products have at the end of their useful life. The main goal is to make a profit (Burton, 2007) through reducing costs or increasing prices. The drive for profits leads companies to focus on obtaining materials at the cheapest possible cost, which often comes at the expense of Planet Earth. This unseen cost (from an accounting point of view) comes to light when we look at the amount of waste we find at a landfill site, in the oceans and on our streets. In 2018 approximately 146.1 million tonnes of waste were landfilled (USEPA, 2021) It isn’t till we consider the environmental costs that we can truly see the overall cost.

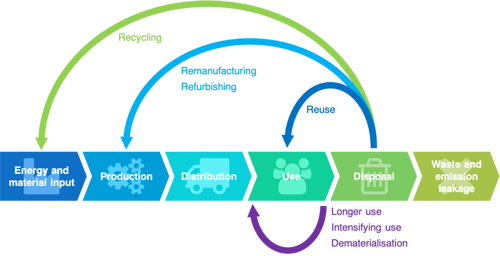

In recent years we have adapted the straight-line economy to add a recycling element to it. This is when instead of disposing of the products after use they are then broken down and used in the production of new goods. These new goods are usually less valuable than the initial product. Within a recycling economy it is expected that the value of material lessens over time till it eventually becomes waste – the aim is to prolong the life of the material so less goes to waste as quickly and we take fewer natural resources in the production process.

A Circular economy eliminates as much waste as possible, ideally the products are built in such as way they can be reused infinitely at their highest level of value. Recycling it into new products is the next option with landfill being a last resort (rather than the first point of call that it currently is). The aim here is to maximise the longevity of the initial resource we take from the planet.

Another idea behind the circular economy is that of sharing or having a good or service be in use 24/7. For example, in the UK there are 32.6 million registered cars with an average of 1.2 cars per household (Nimblefins, 2021). Much of the public us their cars twice a day between the hours of 7-9am and 5-7pm when they are traveling to work. Outside of these times the car is stationary in a carpark or driveway not being used. A circular economy promotes the idea that there needs to be a system of transport that only exists when it is in use or the cars that are parked in the carparks are then used by other throughout the day or evening. This way we are maximising the resources we take from the planet rather than letting them sit there.

A circular economy looks as such

(Geissdoerfer, et al., 2020)

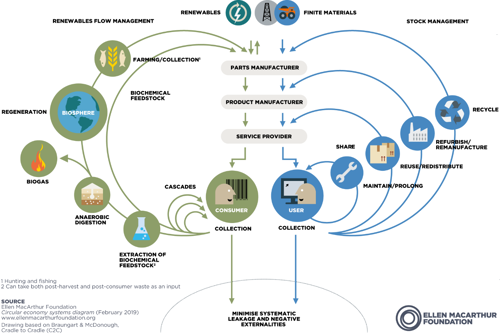

In a circular economy there are two cycles: the technical cycle and the biological cycle

The biological cycle is where consumption of materials occur, biological based materials are designed to feed back into the system through process such as anaerobic digestion and composting. By feeding back into the system we can regenerate living systems such as soils or the oceans. These living systems can also create renewable energy which can then be used within the economy.

Whereas the biological cycle aims to feed the resources back into economy the goal technical cycle is to keep the products in circulation for as long as possible through sharing, repairing and reuse. (Ellen Macarthur Foundation, 2019)

If we take a mobile phone as an example, we see a new phone being released every year with many consumers purchasing the newer model and trading in the older model. These older models are then clean and repaired ready for resale or recycled for use in other models. Whilst this model utilises the ethos of a recycling economy the industry is still using the earth’s natural resources to produce the newer model. The question is do we have enough mobile phones in circulation so that everyone can have access to one without everyone buying a newer model. It is estimated that up to $57 billion worth of materials are discarded every year with approximately 80% of this never being collected for reuse or recycling (Botwright & Pennington, 2020)

The ‘Butterfly Diagram’

The ‘butterfly diagram’ below taken from the Ellen Macarthur Foundation highlights these two cycles and how materials and goods are circulated round the economy. You can clearly see the steps that we can take to minimise the amount of waste and negative outcomes. The diagram is based off Brangart & McDonough Cradle to Cradle.

If we move to a circular economy, we can start to reverse some of the damage that we have done to our planet by minimising our future impact. We can reduce the number of resources we take from the earth and start reuse and recycle the materials we have already extracted. If we do not consider moving to a circular economy, then we will eventually run out of resources to produce new products.

What can I do?

As an individual we can look at put purchasing and disposal habits. Ask yourself the following questions when buying or disposing of items

When buying

- Do I need to buy it?

- Can I buy it second hand?

- Can I borrow it off someone else?

- Can I buy it from a company that uses recycled or refurbished materials.

When disposing of

- Do I need to get rid of the item or can I repair it?

- Can I sell it?

- Can it be reused?

- Can it be recycled by somebody? (You may have to have a look online)

For more information of the circular economy, you can check out some of the articles we have been reading at NuGreen by subscribing to our newsletter below

Sources

Botwright, K. & Pennington, J., 2020. Will your next phone be made from recycled materials? These 6 tech giants are working on it.. Digital Summit, World Economic Forum.

Burton, W., 2007. Burton's Legal Thesaurus (4 ed.). In: s.l.:s.n., p. 68.

Ellen Macarthur Foundation, 2019. https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/. [Online]

Available at: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/

[Accessed Febuary 2022].

Geissdoerfer, M., Pieroni, M. P., Pigosso, D. C. A. & Soufani, K., 2020. Circular business models: A review. Journal of cleaner production.

Nimblefins, E. Y., 2021. Number of Cars in the UK 2022. [Online]

Available at: https://www.nimblefins.co.uk/cheap-car-insurance/number-cars-great-britain

[Accessed 4 March 2022].

USEPA, U. S. E. P. A., 2021. National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling, s.l.: s.n.

Weetman, C., 2016. A Circular Economy Handbook for Business and Supply Chains: Repair, Remake, Redesign, Rethink. s.l.:s.n.

All Images take from Unsplash.com

Written By Joshua Holland